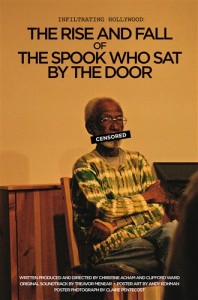

[for the Old Mole 3/26] The Spook Who Sat by the Door is a film released in 1973 about the first Black CIA agent, who, like so many of those trained by the Agency, turns his skills against the US government. Directed by Ivan Dixon, it was based on the 1969 novel of the same title by Sam Greenlee, and is the subject of a recent documentary, Infiltrating Hollywood: The Rise and Fall of the Spook Who Sat by the Door, scheduled to be aired on the Documentary Channel next month.

The title is a triple pun: the term "spook" is an epithet for black people, a term for an espionage agent, and an evocation of the haunting of white America's imagination by the specter of black rebellion and revolution.

Written and directed by African-Americans, the film is a satiric tale of racism and black nationalist rebellion in the United States; it invokes the classic tropes of black invisibility and masking, and, both in its story and in its production, illustrates the power of grassroots organizing and uprising, as well as the resistance governments offer to such uprisings, through both dividing communities and violently repressing them.

Often grouped with blaxploitation films of the era, The Spook Who Sat By the Door shares their low-budget production values as well as some of their sexism and homophobia, but it is far more explicitly political, celebrating not the individual outlaw but the collective power of community organization and the value of global analysis to local struggle. It is, in short, still very timely. It also has a fabulous soundtrack by Herbie Hancock.

The Spook Who Sat By the Door begins in the office of a white Senator whose reelection is threatened by his low poll numbers among black voters, ever since that law and order speech he gave. He wins reelection by attacking the discriminatory hiring policies of the CIA, which has no black officers.

Thus pressured to hire black agents, the CIA starts a recruiting program, expecting all of their recruits to flunk the rigorous training, and keeping them under surveillance to make sure.

But one of the men, the seemingly mild-mannered but significantly named Dan Freeman, played by Lawrence Cook, knows enough to maintain his mask. When one of the other recruits accuses him of being an Uncle Tom he points out that "none of us were picked for our militancy." When it becomes clear to the CIA brass that Freeman is likely to make it through the training, the agent in change comments, “Somehow I forgot Freeman even existed, he has a way of fading into the background.” And it's by manipulating that invisibility, that mask, that he obtains training in weapons, demolitions, and martial arts, guerrilla warfare and clandestine operations.

When he's assigned to be the Agency’s “new top secret reproduction center section chief”--that is, to run the copy machine in the basement—Freeman continues to observe and learn, his hostile environment repeatedly figured as the long white hallway he walks at CIA headquarters.

He's later assigned to be the General's personal assistant, sitting by the front door as a token of the Agency's claim to racial integration.

After five years, he quits the agency to return to Chicago to work at a social service foundation, but his real goal is retraining his old street gang, the Cobras, as a revolutionary fighting unit. The scenes of the Cobras' training repeat the visual framing of the training scenes at the CIA, but where the Agency recruits wore identical jumpsuits, the Cobras wear assorted revolutionary attire. Freeman teaches them to steal, not from “your black brothers and sisters,” but from “the enemy.” Their access to white establishments is easy: “Remember, a black man with a mop, tray or broom in his hand can go damn near anywhere in this country, and a smiling black man is invisible.”

They rob banks and weapons depots, and they train cells in other cities. Freeman tells them, “What we got now is a colony, what we wanna create is a new nation.” Toward this end, Freeman sees in U.S. Vietnam War-era imperial policies a chance to intervene. “There is no way that the United States can police the world and …us … too,” he argues, “unless we cooperate.”

That cooperation is embodied in Freeman's old friend Dawson, played by J.A. Preston, once a gang member and now a detective and a specialist in “inner city riot control.” Dawson believes in “law and order or we might as well be back in the jungle.” But for Freeman, “The ghetto is a jungle, always has been. You understand, you cannot cage people like animals and not expect them to fight back someday. It has always been an army occupation here, with police badges and uniforms. You and me, a cop and a social worker, we are keepers of this …zoo.”

Freeman fails to recruit Dawson to the Freedom Fighters, but doesn't even seem to try to recruit his old girlfriend Joy, played by Janet League, a social worker who worries that "those people" are going to undermine "everything we've worked for."

But though the film and book excoriate the Black bourgeoisie, middle- and professional- class Blacks deserve credit for enabling the production of the movie. When Richard Daley's Chicago refused permits to film there, the crew practiced guerrilla filming on the Chicago El, and were welcomed by the first black mayor of Gary, Indiana, Richard Hatcher, to shoot most of the outdoor scenes there, with the collaboration of Gary's police and fire services for the riot scenes, and the loan of a helicopter for aerial shots. Unable to gain financing through the usual Hollywood channels, the filmmakers, at the suggestion of Greenlee, who cowrote the script, took the project to the community, and amassed enough small donations to bring the film nearly to completion.

For finishing funds, however, they made a distribution deal with United Artists, using their own kind of masking: they cut together selected scenes that made the film look like a more conventional blaxploitation film, and got the money they needed. For three weeks the film played to packed cinemas in Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, and Oakland. But then it was mysteriously pulled from theaters, and was available only in a few bootleg VHS copies until the DVD was issued in 2004. Greenlee and others associated with the film suggest, persuasively enough, that the FBI pressured the distributor to pull the film, in keeping with other tactics deployed by the Bureau’s Counter Intelligence Program, or COINTELPRO. The filmmakers also report that all copies of the movie had disappeared by 2004, when a negative was discovered, stored, hidden, under a misleading title.

The Spook Who Sat By the Door, both book and movie, are available though the Multnomah County Library, and the documentary Infiltrating Hollywood: The Rise and Fall of the Spook Who Sat by The Door will be shown on the Documentary Channel next month, April 18th and 19th, and is available for sale through their website.

The Spook Who Sat By the Door is also available online.

See it if you can.